- Zoology

- Daily Critter Facts

- For Teachers

- Study Guides

- Diseases & Parasites

- Contact

Understanding the Species Complex

in the Animal Kingdom

Understanding the Species Complex

in the Animal Kingdom

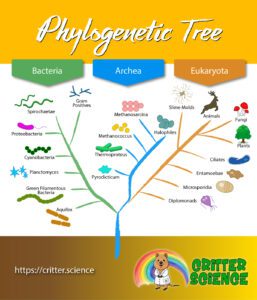

Understanding the species complex in the animal kingdom is critical. In the biological sciences, the classification of life has traditionally relied on morphological characteristics—the observable physical traits of an organism. However, nature is rarely as tidy as human taxonomy would prefer. A “species complex” represents a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance that the boundaries between them are often unclear or blurred. These groups are frequently grouped under a single species name until advanced methods reveal them to be a collection of distinct, yet evolutionarily divergent, lineages. This phenomenon challenges the classical definition of a species and forces biologists to reconsider the true measure of biodiversity on Earth.

Limitations and Similarities

The concept of the species complex highlights the limitations of the “morphological species concept,” which defines species based on shared physical forms. In many cases, evolutionary pressures may drive lineages apart genetically while stabilizing selection keeps their physical appearance virtually identical. These are often referred to as “cryptic species.” While they may look indistinguishable to the human eye, they function as separate biological units, often incapable of interbreeding or separated by distinct behavioral, temporal, or ecological barriers. Recognizing these complexes is not merely an exercise in academic semantics; it is a fundamental step in understanding the operational units of evolution.

The Genetic Drift

The formation of a species complex is often the result of recent evolutionary divergence. When a population becomes separated—perhaps by a geographic barrier like a mountain range or a shift in climate—the isolated groups begin to drift apart genetically. However, if the environmental demands remain similar in both locations, the physical form of the animals may not change significantly, even as their genomes diverge enough to prevent successful hybridization. Consequently, what appears to be a single, widespread species is actually a mosaic of independent evolutionary trajectories, each adapting to its specific micro-environment in subtle ways that are not immediately obvious.

New Tools for the Job

Detecting these complexes requires tools far more sensitive than the ruler and caliper of traditional naturalists. Modern taxonomy relies heavily on molecular phylogenetics, DNA barcoding, and acoustic analysis to peel back the layers of morphological uniformity. For instance, differences in mating calls often precede physical changes in amphibians and insects, serving as a primary reproductive barrier. By analyzing these genetic and behavioral markers, scientists can uncover the “hidden” diversity within a complex, often resulting in one species being split into several new, distinct taxonomic entities.

Morphologies of a Mosquito

One of the most medically significant examples of a species complex is the Anopheles gambiae complex, a group of mosquitoes native to Africa. Historically considered a single species, it is now known to comprise at least 9 morphologically identical but genetically distinct sibling species. While they look the same, they exhibit vastly different behaviors; some breed in saltwater, others in fresh; some feed exclusively on animals, while others prefer humans. This distinction is critical because only certain members of the complex are highly efficient vectors for malaria. Treating them as a single group would lead to ineffective control strategies, as targeting the wrong habitat would fail to suppress the actual disease-carrying populations.

The Giraffe

The recognition of species complexes also has profound implications for conservation status, as seen in the Giraffa camelopardalis complex. For centuries, the giraffe was viewed as a single species with several subspecies scattered across Africa. However, comprehensive genomic studies have suggested that there are actually 4 distinct species of giraffe: the Northern, Southern, Reticulated, and Masai giraffes. When lumped together, the total population might appear stable, but when split, individual species qualify for higher threat categories such as “Endangered.” Recognizing them as separate species ensures that a collapse in 1 specific lineage is not masked by the stability of another.

Varying Responses to Toxins

Similarly, in aquatic toxicology, the freshwater amphipod Hyalella azteca serves as a critical example. Once thought to be a single ubiquitous species, it is now recognized as a complex comprising dozens of cryptic species with varying sensitivities to toxins. If a toxicity test uses a particularly hardy lineage of the Hyalella complex, it might suggest that a pollutant is safe when it is actually lethal to other, more sensitive lineages found in the wild. This variability underscores the importance of precise identification in environmental science to protect the actual biodiversity of aquatic ecosystems.

Clarity and Boundaries Between Lineages

Examples of species complexes are prevalent across the animal kingdom. 1 striking marine example is the bigfin reef squid. While they appear uniform to divers and fishermen, they are actually a cryptic species complex containing multiple distinct lineages. Because the boundaries between these lineages are unclear, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists them as “Data Deficient.” This classification highlights a common problem: we cannot effectively conserve a species if we do not know how many distinct populations actually exist or what their specific population trends are.

Monitors… More Than Meets the Eye

Another example is the Nile monitor. These large, semi-aquatic lizards are found throughout much of Africa and are typically identified by their muscular build and olive-green skin with yellow ocelli. However, they are considered a species complex because the group contains closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance that distinguishing them is notoriously difficult. This ambiguity complicates efforts to study their specific ecological roles and life histories, as data collected for one “species” may actually apply to a genetically distinct sibling species with different behaviors.

The Cutlassfish

The largehead hairtail offers a clear case of how widespread distribution often masks a species complex. Typically considered a single species found in oceans globally, experts argue it’s a complex that includes numerous distinct species, such as the Atlantic, East Pacific, Northwest Pacific (Japanese), and Indo-Pacific cutlassfish. Understanding these distinctions is vital not just for taxonomy but for fisheries management, as these fish are commercially important. Distinct populations may have different growth rates or reproductive cycles, requiring tailored management strategies to prevent overfishing.

Toads and More

Even familiar amphibians like the common toad are not immune to this complexity. While they are a staple of European wildlife, they have descended from a common ancestral line to form a species complex. The borders between these closely related toads are often unclear, blurring the lines of distribution maps. This group serves as a reminder that even animals we think we know well may harbor hidden evolutionary history that complicates their classification.

In Conclusion

The “species complex” is a concept that bridges the gap between static classification and the dynamic reality of evolution. From the malaria-carrying mosquitoes of Africa to the commercially fished hairtails of the Pacific, these complexes reveal that nature is far more diverse than it appears on the surface. Acknowledging and studying these complexes allows scientists to refine conservation strategies, improve disease control, and gain a deeper appreciation for the nuanced and often invisible boundaries that define the animal kingdom.