- Zoology

- Ecology

- Sustainability

- Animal Behavioral Patterns

- What are Species?

- About the Critterman

- Daily Critter Facts

- For Teachers

- Study Guides

- Diseases & Parasites

- Contact

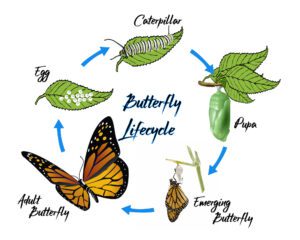

The metamorphosis of a butterfly is 1 of nature’s most profound transformations, a biological overhaul that turns a crawling, earthbound herbivore into a delicate, winged traveler. This process, known as complete metamorphosis (holometabolism), is comprised of 4 distinct stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Each stage is characterized by specific physiological goals and unique survival strategies that ensure the continuation of the species.

The Beginning: The Egg

The cycle begins with a tiny, often overlooked speck: the egg. Female butterflies are remarkably selective, using chemical receptors in their feet to “taste” plants and ensure they lay their eggs on a specific host plant that the future caterpillars can eat. Some species, like the Monarch, are “specialists,” laying eggs exclusively on milkweed, which provides the larvae with chemical defenses against predators.

Form and Function

Butterfly eggs come in an array of shapes and textures—some are ribbed, others spherical or cylindrical. Despite their fragile appearance, the shells (chorion) are tough enough to protect the developing embryo from desiccation (drying out) and minor environmental shifts. Inside, the embryo consumes the yolk, growing until it is ready to breach the shell and enter the world as a larva.

The Larva: The Eating Machine

Once the egg hatches, the larva, or caterpillar, emerges. Its primary and almost exclusive mission is to eat. A caterpillar can increase its body mass by thousands of times in just a few weeks. This stage is defined by rapid growth, as the caterpillar stores the energy and nutrients necessary for the upcoming transformation.

Growth and Molting

Because a caterpillar’s skin (cuticle) does not stretch, it must periodically shed its skin to accommodate its growing body. These stages between molts are called instars. Most butterflies go through 5 instars. During this time, the caterpillar is a sensory specialist, using its simple eyes (stemmata) to find fresh leaves and its silk-spinning spinnerets to create anchors or safety lines on the plant.

Survival and Defense

Caterpillars are vulnerable, making defense a priority. Many species employ mimicry or camouflage to hide from birds. The spicebush swallowtail caterpillar undergoes a “costume change,” looking like a bird dropping in its early stages and later developing large, realistic eyespots to frighten potential predators by mimicking a snake.

Preparation for the Pupa

When the caterpillar reaches its final instar and has stored sufficient fat, it enters a wandering phase. It leaves its host plant in search of a secure, hidden location. Once found, it spins a silk button and attaches its hind legs to it, hanging in a “J” shape. This is the final act of the larval stage before the most dramatic shift begins.

The Pupa: A Hidden Transformation

The transition from larva to pupa (or chrysalis) is not merely a change of clothes; it is a total structural reorganization. The caterpillar sheds its final skin to reveal a hardened shell. Unlike a moth’s cocoon, which is made of silk, the butterfly’s chrysalis is the insect’s own body wall. Inside, the caterpillar’s tissues are broken down by enzymes into a “cellular soup.”

Imaginal Discs

While the body liquefies, specialized clusters of cells known as imaginal discs begin to activate. These cells have been present since the egg stage but remained dormant. They now use the nutrient-rich fluid of the broken-down larval tissue to build the adult structures: wings, long legs, complex eyes, and the proboscis. It is a masterclass in biological recycling.

Emergence: The Eclosion

After a period ranging from days to months, the pupa becomes transparent, revealing the colors of the wings within. The process of the adult butterfly breaking out of the chrysalis is called eclosion. This is a critical moment; the butterfly must emerge quickly and find a place to hang, as its wings are currently wet, crumpled, and useless.

Expanding the Wings

To become flight-ready, the butterfly pumps a fluid called hemolymph through the veins of its wings. If a butterfly cannot hang properly during this stage, its wings may dry deformed, rendering it unable to fly or survive. Within an hour or 2, the wings harden (sclerotize), and the butterfly is ready for its first flight.

The Adult: The Imago

The adult stage, or imago, is focused on reproduction and dispersal. The mouthparts have shifted from the chewing mandibles of a caterpillar to a straw-like proboscis used for sipping nectar. Most adult butterflies live only a few weeks, though some migratory species, like the “Methuselah” generation of Monarchs, can live up to eight months to complete their long journeys.

Completing the Circle

The final act of the lifecycle is the search for a mate. Through a combination of visual displays and pheromones, butterflies find partners to begin the cycle anew. By laying her eggs on the correct host plant, the female ensures that the next generation of “eating machines” has exactly what it needs to survive, maintaining the delicate and beautiful balance of the butterfly’s life history.